Many animals test their legs and totter forth only hours after they are born, but humans need a year before they take their first, hesitant steps. Is something fundamentally different going on in human babies Maybe not. (46) A new study shows that the time it takes for humans and all other mammals to start walking fits closely with the size of their brains.

(47) In past studies to develop a new animal model for the brain s that support motor development, neurophysiologist Martin Garwicz discovered that the schedules by which ferrets and rats acquire various motor skills, such as crawling and walking, are strikingly similar to each other; the progress simply happens faster for rats. That made them wonder how similar the timing of motor development might be among mammals in general.

(48) They compared the time between conception and walking in 24 species and looked at how well this duration correlated with a range of variables, including gestation time, body mass, and brain mass. As they report in this week’s issue of PNAS, brain mass accounts for the vast majority (94%) of the variance in walking time between species.

Species with larger brains, such as humans, tend to take longer to learn to walk. (49) Strikingly, a model based on brain mass and walking time in the other 23 species almost perfectly predicts when humans begin to walk. "We’ve always considered humans the exception," Garwicz says, "But in fact, we start walking at exactly the time that would be expected from all other walking mammals. "

Two other variables—gestation time and brain mass at birth—also correlate nicely with age of walking for most animals, but not for humans. That makes sense, the researchers say: Humans spend an unusually small portion of their development—and build an unusually small fraction of their brain mass—in the womb. (50) The model is able to accommodate this quirk of human development because it uses the time it takes babies to learn to walk from conception, not birth. (At the other extreme, animals such as horses, who have a long gestation and then walk almost immediately after they are born, also fit the model.)

Barbara Finlay, a neuroscientist at Cornell University, says the findings support the existence of a kind of a development "clock" for mammals. In her own work, Finlay has found that various mammals have similar timetables for brain development before birth. But she had imagined that a postnatal milestone such as walking would be more idiosyncratic. "I was surprised," she says. "I thought the clock would start to fracture. " It will be interesting, she says, to see if the clock will keep time for later milestones, such as s related to reproduction.

(48) They compared the time between conception and walking in 24 species and looked at how well this duration correlated with a range of variables, including gestation time, body mass, and brain mass.

Many animals test their legs and totter forth only hours after they are born, but humans need a year before they take their first, hesitant steps. Is something fundamentally different going on in human babies Maybe not. (46) A new study shows that the time it takes for humans and all other mammals to start walking fits closely with the size of their brains.

(47) In past studies to develop a new animal model for the brain s that support motor development, neurophysiologist Martin Garwicz discovered that the schedules by which ferrets and rats acquire various motor skills, such as crawling and walking, are strikingly similar to each other; the progress simply happens faster for rats. That made them wonder how similar the timing of motor development might be among mammals in general.

(48) They compared the time between conception and walking in 24 species and looked at how well this duration correlated with a range of variables, including gestation time, body mass, and brain mass. As they report in this week’s issue of PNAS, brain mass accounts for the vast majority (94%) of the variance in walking time between species.

Species with larger brains, such as humans, tend to take longer to learn to walk. (49) Strikingly, a model based on brain mass and walking time in the other 23 species almost perfectly predicts when humans begin to walk. "We’ve always considered humans the exception," Garwicz says, "But in fact, we start walking at exactly the time that would be expected from all other walking mammals. "

Two other variables—gestation time and brain mass at birth—also correlate nicely with age of walking for most animals, but not for humans. That makes sense, the researchers say: Humans spend an unusually small portion of their development—and build an unusually small fraction of their brain mass—in the womb. (50) The model is able to accommodate this quirk of human development because it uses the time it takes babies to learn to walk from conception, not birth. (At the other extreme, animals such as horses, who have a long gestation and then walk almost immediately after they are born, also fit the model.)

Barbara Finlay, a neuroscientist at Cornell University, says the findings support the existence of a kind of a development "clock" for mammals. In her own work, Finlay has found that various mammals have similar timetables for brain development before birth. But she had imagined that a postnatal milestone such as walking would be more idiosyncratic. "I was surprised," she says. "I thought the clock would start to fracture. " It will be interesting, she says, to see if the clock will keep time for later milestones, such as s related to reproduction.

分享

分享

反馈

反馈 收藏

收藏 举报

举报

【单选题】10() A.accumulates B.amasses C.collects D.gathers

【单选题】What’s the meaning of the word "beeline" in Paragraph 5() A. Winding road. B. Are line. C. Zigzag. D. Straight line.

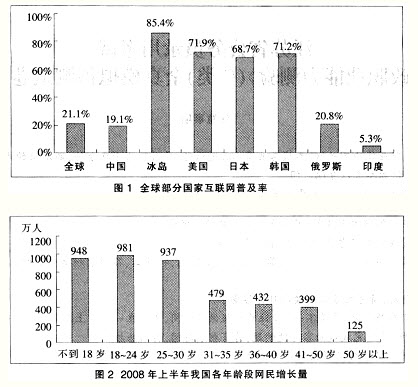

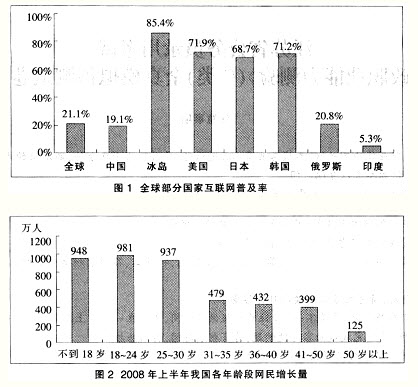

【单选题】2007年7月,我国的网民数量为多少人() A.2.1亿 B.2.05亿 C.1.82亿 D.1.62亿

【单选题】甲公司于2004年注册了“柠檬”商标,该商标被核准使用于电冰箱上。为获取收益,甲公司许可乙公司在其生产的电冰箱上使用“柠檬”商标。为了有效保护该商标,甲公司又申请注册了“白柠檬”、“青柠檬”、“黄柠檬”3件商标。后来,甲公司的电冰箱产品出现了粗制滥造、以次充好、欺骗消费者的现象。丙公司于2008年注册了“小柠檬”商标,也使用于电冰箱上。2010年,甲公司发现丙公司注册并使用“小柠檬”商标的行为。 ...

【单选题】11() A.certain B.critical C.whole D.plus

【单选题】Hostility to Gypsies has existed almost from the time they first appeared in Europe in the 14th century. The origins of the Gypsies, with little written history, were shrouded in mystery. What is know...

复制链接

复制链接 新浪微博

新浪微博 分享QQ

分享QQ 微信扫一扫

微信扫一扫