创建自己的小题库

搜索

【简答题】

Starting over: Rebuilding Civilisation from Scratch

The way we live is mostly down to accidents of history. So what if we thought it through properly

In just a few thousand years, we humans have created a remarkable civilisation: cities, transport networks, governments, vast economies full of specialised labour and a host of cultural labels. It all just about works, but it’s hardly a model of rational design--instead, people in each generation have done the best they could with what they inherited from their predecessors. As a result, we’ve ended up trapped in what, in review, look like mistakes. What sensible engineer, for example,would build a sprawling, low-density megalopolis (巨大城市) like Los Angeles on purpose

Suppose we could try again. Imagine that Civilisation 1.0 evaporated tomorrow, leaving us with unlimited manpower, a willing populace and--most important--all the knowledge we’ve accumulated about what works, what doesn’t, and how we might avoid the errors we got locked into last time. If you had the chance to build Civilisation 2.0 from scratch, what would you do differently

Take cities, for starters. Historically, they have generally arisen near resources that were important at the time-say harbours, farmland or minerals--and then grown higgledy-piggledy (杂乱无章的). How would we design cities without the constraints of historical development

In many ways, the bigger cities are, the better. City dwellers have, on average, a smaller environmental footprint than those who live in smaller towns or rural areas. Indeed, when Geoffrey West of the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico and his colleagues compared cities of different sizes, they found that doubling the size of a city leads to a 15 per cent decrease in the energy use per capita, the amount of roadway per capita, and other measures of resource use. For each doubling in size,city dwellers also benefit from a rise of around 15 per cent in income, wealth, the number of colleges,and other measures of socioeconomic well-being. Put simply,bigger cities do more with less.

Of course,there are limits to a city’s size. For one thing, West notes, his study leaves out a crucial part of the equation:happiness. As cities grow, the increasing buzz that leads to greater productivity also quickens the pace of life. Crime, disease, even the average walking speed, also increase by 15 per cent per doubling of city size. "That’s not good, I suspect, for the individual," he says. "Keeping up on that treadmill (跑步机), going faster and faster, may not reflect a better quality of life."

City living

Today,online social networking gives individual users tools to coordinate and cooperate like never before. "I would build the cities in an open-source way, where everybody can actually participate to decide how it’s used and how it changes," says Carlo Ratti, an designer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "It’s a similar process to what happens in Wikipedia." By tapping into this sort of crowd-sourcing, the residents themselves could help plan their own wiki-neighbourhood, Ratti proposes. An entrepreneur seeking to start a sandwich shop, for example, could consult residents to find out where it is most needed. Likewise, developers and residents could collaborate in deciding the size, placement and amenities for a new housing block--even, perhaps, the placement of roads and walking paths.

Referring to the problem of energy, virtually everyone agrees the answer should be renewables. "We can’t say it should all be solar or it should all be wind. It’s really critical that we have all of them," says Lena Hansen, an electric system yst with the Rocky Mountain Institute, an energy-efficiency think tank in Boulder,Colorado. That would help ensure a dependable supply. And instead of massive power plants, the best route would be small dispersed systems like rooftop solar panels. This decentralised generation system would be less vulnerable to extreme s like storms or attacks.

While we’re messing around with the economy, we might want to move away from using GDP as a measure of success. When nations began focusing on GDP after the second world war, it made sense to measure an economy by its production of goods and services. "At that time, what most people needed was stuff. They needed more food, better building structures--stuff that was lacking--to make them happy," says Ida Kubiszewski of the Institute for Sustainable Solutions at Portland State University in Oregon. "Now times have changed. That’s no longer the limiting factor to happiness."

Instead, we may want to broaden our indicator to include environmental quality, leisure time, and human happiness-- a trend a few governments are already considering. With Gross Domestic Happiness as our guide, people might be more likely to use gains in productivity to reduce their work hours rather than increase their salaries. That may sound utopian, but at least some societies routinely put greater value on happiness than on material things--such as the kingdom of Bhutan and the aboriginal potlatch (冬季赠礼节) cultures of the west coast of North America that redistribute their property. "I don’t think it’s contrary to human nature to have a system like this," says Robert Costanza, an ecological economist also at Portland State.

New world view

On the other hand, increases in mobility, communication and technology--as well as the sheer size of the human population--mean that many of the world’s problems are now truly global. Just as s drove medieval city states to integrate into nations centuries ago, global problems are now pressing for global solutions, he says. And that requires some form of global governance, at least to set broad g0als--biodiversity standards, say, or global emissions caps--toward which local governments can find their own solutions.

All our design efforts to this point have been aimed at creating a sustainable, equitable and workable new civilisation. But if we want our new society to last through the ages,many sustainability researchers stress one more point: be careful not to make it too efficient.

In the end, though, no human civilisation can last forever. Every society encounters problems and solves them in whatever way seems most helpful, and every time it does so, it raises its complexity--and its vulnerability." You can never fully anticipate the consequences of what you do," notes Tainter. Every civilisation sows the seeds of its own ual doom--and no matter how carefully we plan our new built-from-scratch civilisation, the most we can hope for is to delay the inevitable.

Starting over: Rebuilding Civilisation from ScratchIn creating a sustainable,equitable and workable civilization,we also need to be careful not to______.

分享

分享

反馈

反馈 收藏

收藏 举报

举报参考答案:

举一反三

【单选题】生物种类的灭绝是一个依赖于生态、地理和生理变量的过程。这些变量以不同的方式影响不同种类的有机体,因而灭绝的方式应该是杂乱无章的。然而,化石记录显示生物以一种令人惊奇的确定的方式灭绝,很多种群同时消失。 以下哪一项如果是正确的,为化石所记录的灭绝方式至少提供了部分解释( )

A.

主要的灭绝发生期是由于影响很多不同种群的范围很广的环境变化引起的。

B.

一些种群灭绝了是因为它们的当地环境逐渐积累的变化。

C.

在地理上最近一段时间,没有什么化石记录,人们的干预已经改变了灭绝的方式。

D.

那些广泛分布的种群最不可能灭绝。

【单选题】道路密度指的是在一定区域内,道路网的总里程与该区域面积的比值。平均车行速度是指某地区各种汽车的平均行车速度。下图是某特大城市道路密度和平均车行速度等值线图,甲地的值可能为()

A.

4.6

B.

5

C.

3.1

D.

3.8

【单选题】规划人口在200万以上的大城市,城市道路用地面积应占城市建设用地面积的比例为 ( )。

A.

7%~10%

B.

8%~15%

C.

15%~20%

D.

20%~25%

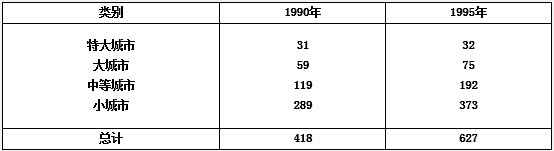

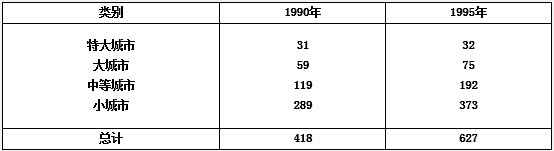

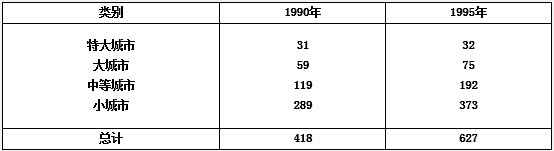

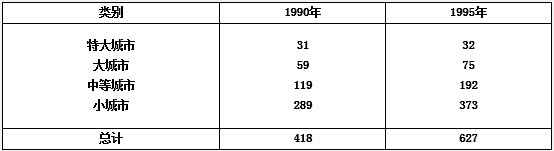

【单选题】1990-1995年我国城市发展烽目 1990~1995年中增长速度最慢的城市是()。 A.特大城市 B.大城市 C.中等城市 D.小城市

A.

1990-1995年我国城市发展烽目

B.

【单选题】群租房的租客,多是低收入的流动人口。留在大城市,对他们意味着更多的机会、更高的收入;对他们家人意味着更 的文化医疗资源,以及代际贫困的梦想;对城市则意味着 更便宜的劳动力、更丰富的创造力。可他们买不起大城市的商品房,又住不进供给有限、门槛颇高的保障房。面对近三年来持续上涨的住房租金,群租房里一张简陋的单人床,自然成了 选择。 依次填入画横线部分最恰当的一项是( )。

A.

优厚 脱离 必须

B.

优越 摆脱 无奈

C.

丰富 实现 无助

D.

优越 成就 必备

【单选题】虽然我国农村一对夫妇大多生育二胎以上,但几乎所有的年轻人都一拨一拨地到城市打工。因此,年轻的高素质移民将不断对冲大城市老龄人口,使人口年龄相对下降或持平,这样,大城市的活力就会保持下去。而在一些地方,老年人支撑农村,已显端倪,甚至可能成为常态。日本的偏僻农村就是前车之鉴。这段文字说明:

A.

中国的人口老龄化问题与日本同样严重

B.

农村可能比大城市更早进入老龄化时代

C.

人口状况直接决定一个地区的发展

D.

人口流动将加剧城乡发展的不均衡性

相关题目:

【单选题】生物种类的灭绝是一个依赖于生态、地理和生理变量的过程。这些变量以不同的方式影响不同种类的有机体,因而灭绝的方式应该是杂乱无章的。然而,化石记录显示生物以一种令人惊奇的确定的方式灭绝,很多种群同时消失。 以下哪一项如果是正确的,为化石所记录的灭绝方式至少提供了部分解释( )

A.

主要的灭绝发生期是由于影响很多不同种群的范围很广的环境变化引起的。

B.

一些种群灭绝了是因为它们的当地环境逐渐积累的变化。

C.

在地理上最近一段时间,没有什么化石记录,人们的干预已经改变了灭绝的方式。

D.

那些广泛分布的种群最不可能灭绝。

【单选题】道路密度指的是在一定区域内,道路网的总里程与该区域面积的比值。平均车行速度是指某地区各种汽车的平均行车速度。下图是某特大城市道路密度和平均车行速度等值线图,甲地的值可能为()

A.

4.6

B.

5

C.

3.1

D.

3.8

【单选题】规划人口在200万以上的大城市,城市道路用地面积应占城市建设用地面积的比例为 ( )。

A.

7%~10%

B.

8%~15%

C.

15%~20%

D.

20%~25%

【单选题】1990-1995年我国城市发展烽目 1990~1995年中增长速度最慢的城市是()。 A.特大城市 B.大城市 C.中等城市 D.小城市

A.

1990-1995年我国城市发展烽目

B.

【单选题】群租房的租客,多是低收入的流动人口。留在大城市,对他们意味着更多的机会、更高的收入;对他们家人意味着更 的文化医疗资源,以及代际贫困的梦想;对城市则意味着 更便宜的劳动力、更丰富的创造力。可他们买不起大城市的商品房,又住不进供给有限、门槛颇高的保障房。面对近三年来持续上涨的住房租金,群租房里一张简陋的单人床,自然成了 选择。 依次填入画横线部分最恰当的一项是( )。

A.

优厚 脱离 必须

B.

优越 摆脱 无奈

C.

丰富 实现 无助

D.

优越 成就 必备

【单选题】虽然我国农村一对夫妇大多生育二胎以上,但几乎所有的年轻人都一拨一拨地到城市打工。因此,年轻的高素质移民将不断对冲大城市老龄人口,使人口年龄相对下降或持平,这样,大城市的活力就会保持下去。而在一些地方,老年人支撑农村,已显端倪,甚至可能成为常态。日本的偏僻农村就是前车之鉴。这段文字说明:

A.

中国的人口老龄化问题与日本同样严重

B.

农村可能比大城市更早进入老龄化时代

C.

人口状况直接决定一个地区的发展

D.

人口流动将加剧城乡发展的不均衡性

参考解析:

AI解析

重新生成

题目纠错 0

发布

复制链接

复制链接 新浪微博

新浪微博 分享QQ

分享QQ 微信扫一扫

微信扫一扫